Most criminal offenses in Texas have some sort of mental state requirement. These are sometimes referred to as “culpable mental states” or “mens rea” which is Latin for “guilty mind.” The possible mental states in Texas criminal law are:

- Intentionally

- Knowingly

- Negligently

- Recklessly

- No Mental State Required

You generally cannot commit a crime purely on accident. You must have some level of mental awareness, sometimes even just very slight, that your actions are criminal or may result in some negative result that could be considered criminal under the law. The exceptions are offenses for which no mental state is required (such as DWI.) Criminal offenses are presumed to have a mental state requirement and are not presumed to be strict liability offenses. See Aguirre v. State, 22 S.W.3d 463, 471-472 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999).

What does “Intentionally” mean in Texas Criminal Law?

From Texas Penal Code 6.03 (a), we know “intentionally” for result-oriented crimes means it was the person’s conscious objective or desire to cause the result. Intentionally for a conduct-oriented crime means it was the person’s conscious objective or desire to cause the result.

What does “Knowingly” mean in Texas Criminal Law?

From Texas Penal Code 6.03(b), “knowingly” for a result-oriented crime means that the person is aware that his conduct is reasonably certain to cause the result. Knowingly for a conduct-oriented crime means that the person is aware of the nature of his conduct or that the circumstances exist.

What does “Recklessly” mean in Texas Criminal Law?

Pursuant to Penal Code 6.03 (c), “recklessly” for a result-oriented crime means that the person is aware of but consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the result will occur. Recklessly for a conduct-oriented crime means that the person is aware of but consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the circumstances exist. Under both definitions, the risk must be of such a nature and degree that its disregard constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of care that an ordinary person would exercise under all the circumstances as viewed from the actor’s standpoint.

What does “Negligently” mean in Texas Criminal Law?

Under Penal Code 6.03 (c), “criminal negligence” for a result-oriented crime means a person acts when he ought to be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the result will occur. Criminal negligence for a conduct-oriented crime means a person acts when he ought to be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the circumstances exist. For both definitions, the risk must be of such a nature and degree that the failure to perceive it constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of care that an ordinary person would exercise under all the circumstances as viewed from the actor’s standpoint.

2024 Supreme Court Update:

The Supreme Court issued its opinion in Diaz v. United States changing the framework for admissibility of expert testimony regarding mens rea.

Example of the Differences Between the Mental States

The best way to explain the difference between intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, and negligently is through an example. Let’s imagine you are in a hotel room several stories up from the street. Imagine the hotel is in a busy downtown area. Now imagine taking the television from the hotel room and setting it on the ledge of the open window. Now:

- Intentional – It would be an intentional act to look out the window, see a busy street, take aim, and push the television so it falls directly a person.

- Knowing – It would be a knowing act to look out the window, see a busy street, and push the television off the ledge. You do not intend hit anyone, but you were aware that it was reasonably certain a person would be struck and injured.

- Negligent – It would be a negligent act to know that there is a busy street below, consciously choose not to look out to see if it was busy at the time, and push the tv off the ledge – you were aware of but consciously disregarded a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the result of hurting someone would occur.

- Reckless – It would be reckless to push the tv out of a hotel window without knowing or checking what was below. Here, you ought to have been aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the result of hurting someone would occur.

The culpable mental states for offenses drive the level of many offenses, and therefore the punishment range of an alleged offense. It could also make a difference as to whether the act is an offense at all. One of the most common mistakes defense attorneys make is not getting the correct language in a jury charge – for example, giving the jury both definitions when only a result-oriented or conduct-oriented definition should be given.

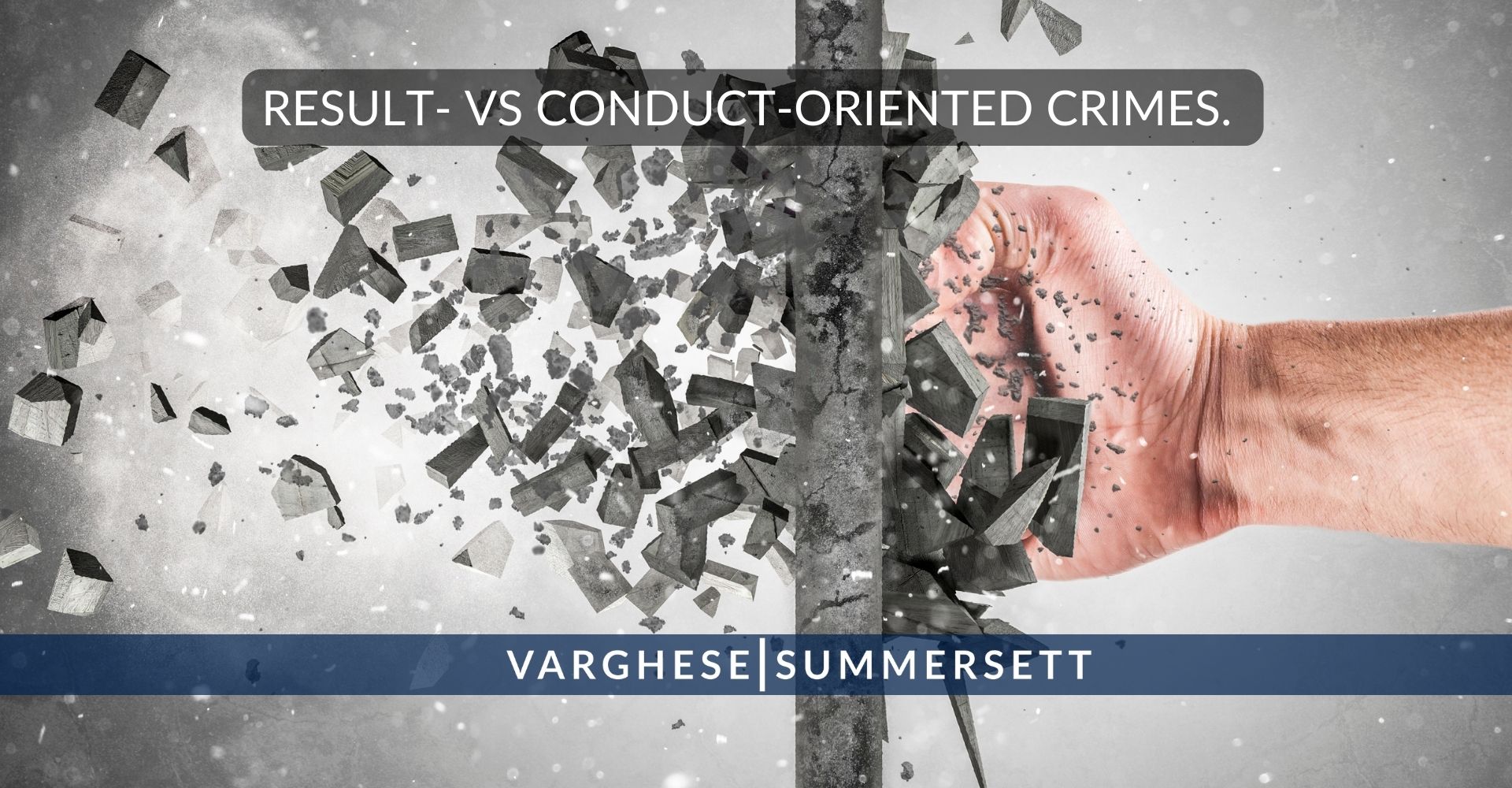

Result-Oriented Crimes vs. Conduct-Oriented Crimes

In determining whether a crime is result-oriented, conduct-oriented, or both, courts must look to the gravamen—the gist—of the offense. An offense can be both result-oriented and conduct-oriented if it has multiple gravamina focusing on both conduct and results.

Result-Oriented vs. Circumstance-Oriented Crimes in Texas

In Texas criminal law, understanding the distinction between result-oriented and circumstance-oriented crimes is essential for proper legal analysis, jury instructions, and determining the sufficiency of evidence. This framework, significantly clarified by the Lugo-Lugo v. State case, helps identify what the prosecution must prove regarding the defendant’s mental state.

Result-Oriented Crimes

Result-oriented crimes focus on the outcome or consequence of the defendant’s actions. The culpable mental state (intentionally, knowingly, recklessly, etc.) must apply to the result element of the offense. Some key points about result-oriented crimes in Texas include:

- Murder: This is a prime example of a result-oriented crime where the death of the victim is the gravamen (essential element) of the offense. The prosecution must prove that the defendant intended or knew that their actions would result in the victim’s death.

- Injury to a Child: Here, the focus is on the harm caused to the child. The prosecution must demonstrate that the defendant’s actions were intended to or knowingly caused injury.

- Assault: For assault to be considered result-oriented, the prosecution needs to show that the defendant intended to cause bodily injury.

In result-oriented crimes, the defendant’s awareness or intent regarding the prohibited result is crucial, not just the conduct itself.

Circumstance-Oriented Crimes

Circumstance-oriented crimes, on the other hand, focus on the circumstances surrounding the defendant’s conduct rather than a specific result. For these offenses:

- Child Abandonment: The key element is the circumstances of exposing the child to an unreasonable risk. The prosecution must prove that the defendant knowingly left the child in a situation that exposed them to potential harm.

- Theft: This crime requires knowledge of the circumstances, specifically that the property taken belongs to another person. The prosecution must show that the defendant was aware of the nature of their actions and the context in which they were taking the property.

In circumstance-oriented crimes, the culpable mental state must apply to the circumstances surrounding the conduct, emphasizing the defendant’s awareness of the context in which their actions took place.

The Lugo-Lugo Case

The Lugo-Lugo v. State case played a pivotal role in establishing this framework by emphasizing that different “elements of conduct” – including the nature of conduct, circumstances surrounding conduct, and result of conduct – may require different culpable mental states. The court held that for circumstance-oriented crimes, an additional culpable mental state is required for the circumstances surrounding the conduct.

Importance of the Distinction

This distinction is important for several reasons:

- Jury Instructions: Properly identifying whether a crime is result-oriented or circumstance-oriented is crucial for guiding the jury in understanding what the prosecution must prove.

- Sufficiency of Evidence: It affects the analysis of whether the evidence presented is sufficient to meet the required legal standards for the defendant’s culpability.The courts continue to refine and apply this framework across various offenses, ensuring that the legal standards for culpable mental states are appropriately matched to the elements of each crime.

Result- and Circumstance-Oriented Offense Examples

| Crime | Circumstance- or Result-Oriented | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Aggravated Sexual Assault | Circumstance-Oriented | Fields v. State, 966 S.W.2d 736 (San Antonio 1998) |

| Assault | Circumstance-Oriented | Murray v. State, 804 S.W.2d 279 (Fort Worth 1991) |

| Burglary | Circumstance-Oriented | Guzman v. State, 988 S.W.2d 884 (Corpus Christi 1999) |

| Deadly Conduct | Circumstance-Oriented | Ford v. State, 38 S.W.3d 836 (Houston [14th Dist.] 2001) |

| Indecency (Contact) | Circumstance-Oriented | Johnson v. State, 967 S.W.2d 848 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) |

| Indecent Exposure | Circumstance-Oriented | Asemota v. State, 996 S.W.2d 322 (Houston [14th Dist.] 1999) |

| Injury to Elderly | Circumstance-Oriented | Kelly v. State, 748 S.W.2d 236 (Tex. Crim. App. 1988) |

| Robbery | Circumstance-Oriented | Ash v. State, 930 S.W.2d 192 (Dallas 1996) |

| Securities Fraud | Circumstance-Oriented | Cook v. State, 824 S.W.2d 634 (Dallas 1991) |

| Sexual Assault | Circumstance-Oriented | Pitre v. State, 44 S.W.3d 616 (Eastland 2001) |

| Theft | Circumstance-Oriented | Skillern v. State, 890 S.W.2d 849 (Austin 1994) |

| Aggravated Assault | Result-Oriented | Schultz v. State, 923 S.W.2d 1 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996) |

| Aggravated Assault by Threat | Result-Oriented | Cole v. State, 46 S.W.3d 427 (Fort Worth 2001) |

| Assault by Threat | Result-Oriented | Fuller v. State, 819 S.W.2d 254 (Austin 1991) |

| Indecency (Exposure) | Result-Oriented | Ex Parte Guinther, 982 S.W.2d 506 (San Antonio 1998) |

| Injury to a Child | Result-Oriented | Hoggins v. State, 785 S.W.2d 827 (Tex. Crim. App. 1990) |

| Murder (§19.02(b)(1)) | Result-Oriented | Cook v. State, 884 S.W.2d 485 (Tex. Crim. App. 1994) |

| Murder (§19.02(b)(2)) | Result-Oriented | Ramirez v. State, 976 S.W.2d 219 (El Paso 1998) |

| Prostitution | Result-Oriented | Mattias v. State, 731 S.W.2d 936 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987) |